How today’s trauma can affect future generations – and how to stop it

We are currently living through a confluence of mass trauma events: a global pandemic; oppressive forces of white supremacy; a dangerously partisan political environment; an escalating climate crisis. Mounting evidence suggests that once some of these disasters ebb, the trauma they have inflicted can have lingering effects, even on future generations.

In other words, the current and future offspring of people living through today’s panoply of horrors may well suffer from it even without their own memories of events.

In the United States alone, 23.2 million people have been diagnosed with COVID-19, and more than 385,000 people have died from it, making it the country with the highest number of deaths worldwide, growing daily.

On top of that, the past year has seen multiple killings of Black people by police, leading to historically large and widespread protests against the ongoing legacies of racism in America, generations of racism brought to bear.

Undergirding all this is an ever-escalating climate crisis that wreaked extreme storm damage across the gulf just as COVID made it dangerous to house climate refugees en masse.

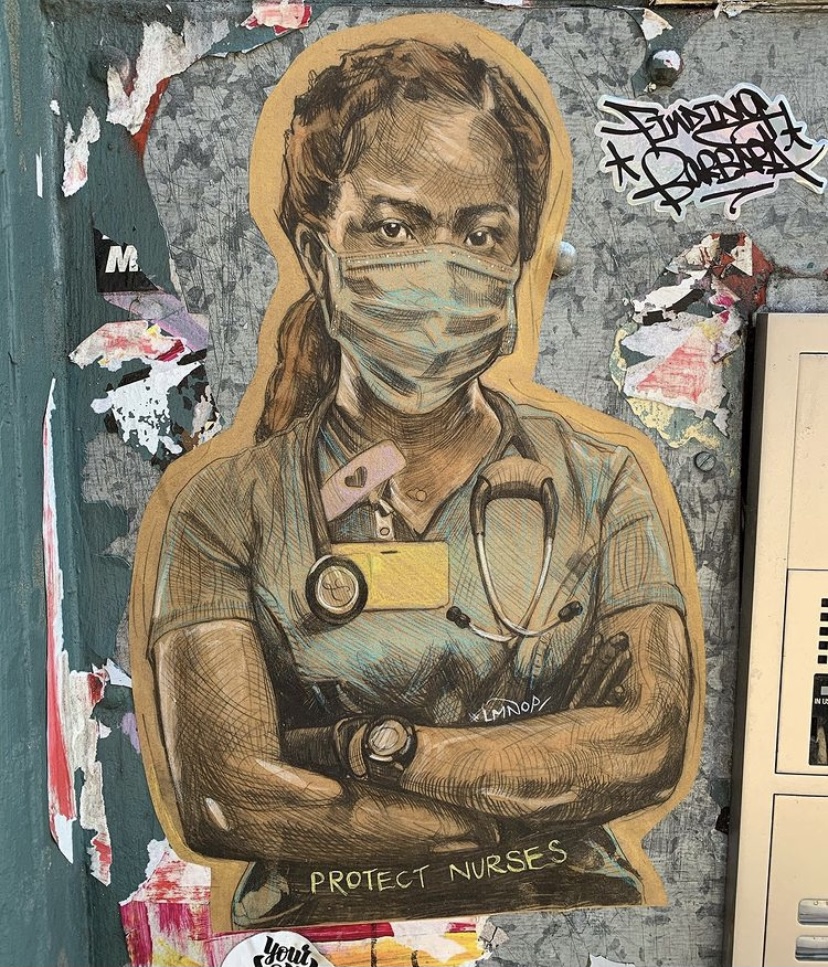

The trauma risks to frontline workers, especially healthcare workers during COVID, have already been documented. But the effects 2020 will have on the rest of us are still playing out, and research suggests that those effects may echo far beyond the current generation.

Past studies have indicated an association between parental PTSD and secondary trauma in offspring of refugees, torture victims, and combat veterans, among others.

There is growing recognition in psychology of secondary trauma, where a person experiences post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms via proximity to someone else’s harrowing experience. That is, you don’t need to experience a potentially traumatic event directly to suffer psychological symptoms from it, because learning about terrible things happening to loved ones can trigger reactions akin to experiencing it first-hand. Past studies have indicated an association between parental PTSD and secondary trauma in offspring of refugees (Sangalang & Vang, 2017), torture victims (Daud et al., 2005), and combat veterans (Dekel & Goldblatt, 2008; O’Tool et al., 2016), among others.

In other words, the current and future offspring of people living through today’s panoply of horrors may well suffer from it even without their own memories of events.

A recent research paper published in Traumatology further supports the grim notion that traumas have the potential to affect the children of those who have survived them (Payne & Berle, 2020). The paper is a meta-analysis -- the study of multiple research papers at once, looking for larger trends across data sets -- of prior studies on PTSD in children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. The researchers found that children, but not grandchildren, of survivors are more likely than the general population to display trauma symptoms.

It’s unclear how trauma is passed from one generation to the next. Trauma could be hereditary, perhaps through stress hormones, or children may internalize their parents’ trauma through observing behavioral and emotional patterns. Trauma may even be passed down through how parents communicate or interact with their kids. The authors recommend that future studies parse these possibilities further. Regardless, the paper further strengthens the case that if parents suffer from PTSD, their children are more likely to have symptoms, too.

We can’t always stop terrible things from happening to us, but we can, with help, go from strength to strength.

This growing problem has a solution: As we navigate this historically troubling era, we must prioritize systematic screening for – and increasing access to – trauma treatment, notably for the people of color who have long been shut out of our current system. PTSD is treatable, and no one should have to suffer when there are evidence-based treatments that actually work and can prevent trauma’s passage to survivor offspring.

What’s more, working through trauma has additional benefits -- treatment opens a person up to experiencing posttraumatic growth, an experience of positive psychological change as a result of going through a challenging event. People I’ve worked with who have experienced this talk about having increased resilience, empathy, and improved relationships. We can’t always stop terrible things from happening to us, but we can, with help, go from strength to strength.

About Us

At Center Psychology Group in New York, we specialize in providing compassionate and evidence-based therapy tailored to your unique needs. Whether you’re seeking EMDR therapy, Somatic Experiencing, or integrative trauma-informed psychotherapy, our experienced team is here to support you. Learn more about our services and how we can help you on the path to healing. Ready to take the next step in your healing journey? Book a free 15-minute phone consultation here.